- The Dodo Club Newsletter

- Posts

- The Dodo Club (49th Edition)- Making Good Money (2) – Enterprise Value (and Art)

The Dodo Club (49th Edition)- Making Good Money (2) – Enterprise Value (and Art)

5 Considerations in Generating Value

A note from me

Hi Folks,

It has been a challenging fortnight, but there have been some bright spots. In the last Newsletter, I noted that my wife had fallen and sustained a Monteggia Fracture of the arm. This required surgery and the insertion of some serious titanium plates – she’s now essentially a cyborg!

Seriously, though, she’s still in a lot of discomfort from the breaks and the surgery, so we have to be careful to avoid knocks or movements that can make the situation worse. I am slowly learning to be a better carer!

While our holiday plans are up in smoke, we have still been able to get out to the cinema. We recently saw a low-budget piece called The North.

Some people will dislike this film as it’s slow-moving, but I found the experience grew on me and became almost profound in moments. It’s a Dutch production and director (Bart Schrijver), with Dutch (Bart Harder) and Spanish (Carles Pulido) lead actors, and the dialogue is predominantly English.

For the first 30 minutes, I felt it was a 7 out of 10 on the “Jeremy scale”, then by halfway it seemed an 8, and by the end I felt it reached almost a 9.

There is no obvious plot, just a journey. Two friends, who haven’t seen each other for a decade, reconnect by hiking 600 km across the wilds of Scotland. They, and we, are confronted by the implacable, indifferent, immense scale, power, challenge and occasional beauty of the landscape, and are slowly affected by this. The film surfaces the difficulty many men have in expressing important things to each other, in understanding, articulating and dealing with their own emotions, and in revealing themselves and their vulnerabilities to those close to them. They do things rather than say things. I write “men” rather than “people” because these are traits I know well and recognise in myself and others, and Mary also feels that way - that most women would have handled the situations in the film differently. In fact, they probably wouldn’t have chosen to reconnect by going on a 600 km hike in the first place!

This Newsletter may feel like a bit of a harder slog than typical editions, with its inclusion of financial terms and charts, but I hope you find reading it a valuable experience as much as I found it worthwhile to stay with The North. It continues to build on threads we have explored previously, aimed at helping you build a better life for yourself and the people around you, despite the current socio-political challenges and disruptions across the world and your own personal challenges. I hope you continue to find all these Newsletters valuable and that they help you enrich your own personal or organisational perspectives.

My Bi-Weekly Guide

Making Good Money – Enterprise Value (and Art)

As explored in the previous Newsletter, the phrase “making good money” can, of course, be interpreted in more ways than one. Whether your own personal emphasis, however, is on the word “money” or on the word “good”, the notions introduced in this series of Newsletters are relevant to both.

Money may only be a medium of exchange in transactions but, outside of coercive situations, those transactions are undertaken because the parties involved see value in the exchanges. That value can manifest in consumption or investment, stimulating additional activity and value generation. The economy grows. Prosperity grows... and spreads. A typical person today enjoys a material quality of life only available to a few aristocrats in days gone by.

Eastern Art has a deeper tradition of explicitly celebrating prosperity as a positive in itself than Western art, which has long been suspicious of money. This may stem from the church tradition that strongly differentiates spiritual and material wealth, drawing on the biblical assertion that the love of money is the root of all evil. Yet, much Western art would not exist without the prosperity that has enabled resources to be invested in its creation and the support of its creators. So, in various ways - often in the background – much Western art also celebrates prosperity.

By now, readers will be familiar with my particular interest in Renaissance art, and one of my favourite examples is the world-famous “Primavera” (Spring) painted by Sandro Botticelli. This beautiful, huge painting on panel can now be found in the Uffizi gallery in Florence, a building that was originally the office for the wealthy (and sometimes ruling) Medici family and was probably initially commissioned by a Medici. It was painted in the 1470s or 1480s while Lorenzo Il Magnifico headed the family and is thought by many to have been painted for his cousin, Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco.

The grace, harmony, scale and simple beauty of the painting caused my spirits to soar both times I have been able to view it in person, despite the surrounding tourist crowds. It is a celebration of abundance and new Spring growth, which, for me, brings a connection with the ideas of prosperity and value. Flora escapes the grasp of the cold wind and becomes Spring, who scatters a profusion of flowers. Venus, Goddess of love, is at the centre with Cupid above her, blessing the three Graces (beauty, joy and creativity), while Mercury drives away the clouds.

The underlying basis for making good money sustainably is to generate value through the powerful commercial engine. This was certainly recognised by the Medici’s who invented much of modern banking practice. Today, commercial assets and organisations are predominantly valued financially by societies through financial markets, so I’ll turn to indicators from such markets to deepen our investigation.

5 Considerations in Generating Value:

Enterprise Value and Capital Employed:

In financial markets, the overall monetary value of a company can be expressed as the value owned by its shareholders plus the value owned by its debtholders. For publicly listed companies, the former can be seen in the market capitalisation of its shares (plus any preferred or minority interests not in the open market). The net debt can be seen from the valuation of the bonds it has issued in bond markets (plus any other borrowings that can be read in its accounts). The total value is referred to as the Enterprise value (EV).

Of course, valuable resources need to have been invested to build that value, and the value of the financial resources invested can be found in the “Capital Employed” (CE) in the accounts. For me, EV and CE are the primary key indicators for describing financial value generation.Value Ratio:

A surplus of Enterprise Value over Capital Employed is a good rough indicator that additional financial value has been generated through the activities of the company. Unfortunately, this is not always a positive surplus, and a deficit is an indicator that investors, at least, currently believe that overall value has been historically eroded.

Of course, companies exist at vastly different scales, so while the absolute size of surplus or deficit is meaningful in itself, the ratio of EV/CE (Value Ratio) is a good approximate yardstick for comparing the effectiveness of value generation for different companies, normalised for scale. If this is greater than 1, the company has greater financial value than the capital that has been invested to build it. Value has been generated. The greater the ratio, the more effective it has been at this.Value generation spectrum:

Different companies will deliver different levels of performance in financial value generation, so we can expect a spectrum of Value Ratios when we look at a selection of different companies. And we also shouldn’t expect these levels to remain static over the course of time.

We live in competitive markets, both real and financial. If a company is particularly successful in doing something that generates revenue, then competitors will be drawn to enter that market themselves, which will drive down the revenues for the original company. Investors will shift their funds elsewhere, and the value ratio will decline. So competitive forces will act against ratios remaining unusually high.

In contrast, if a company is not particularly successful, then either it will go out of business altogether or others will choose to leave an unattractive market, and there will be some recovery. Investors will shift their funds around accordingly.

In total, therefore, there will be both market exits and competitive reversion pressures in both directions. As the investor markets are also competitive, the financial benchmark will be the so-called risk-adjusted “cost of capital”, meaning that investors, on average, receive a return more or less in line with what they have invested. So the enterprise value for the “average” company will be close to its capital employed, meaning that the average Value Ratio for markets will be around “1” (or a little higher on average, taking into account the exit from markets of unsuccessful companies). This tight clustering of values and average level can be seen, for example, below, from the distribution pattern for around 800 energy companies valued in US and European financial markets.

Value generation growth:

Examining the Value Ratio spectrum or distribution, it can be seen that only a very few enterprises are able to generate a level rather greater than 1 or 2, and there are even fewer that can maintain this for a considerable period. For those that do, given that they are subject to very strong competitive forces in both their business and financial markets that constrain this, this inevitably signals that they have developed attractive competitively advantaged positions that can not easily be competed away. I refer to this as securing Competitive Strongholds. Despite challenges from competition, there are some enterprises that have been able to do this, as indicated below for a selection of well-known companies in very different areas of business.

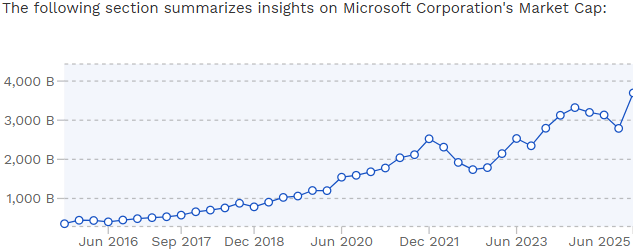

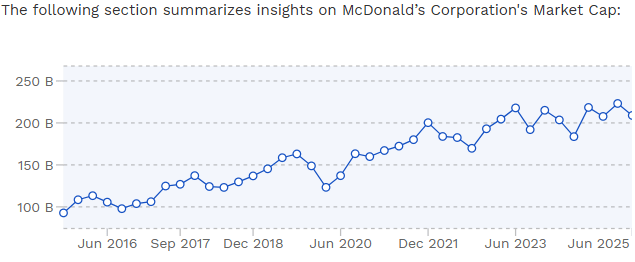

To the extent that these kinds of successful companies can hold and possibly grow their advantaged strongholds, there is the prospect of deploying additional capital to grow their enterprises because investors believe in the prospect of multiplying the investment well beyond the average cost-of capital. This association with additional value growth over the longer term can also be seen in the following charts of Market Capitalisation. As highlighted below, the market value of all these enterprises has doubled, or more, over 10 years.

An indicator of the value growth thesis:

Enterprises will, of course, tend to grow when additional capital is invested in them. Hence, companies with large enterprise value will also generally be associated with large capital employed. In the past, companies in businesses with significant economies of scale and uncommon technology requirements, such as integrated energy majors, would attract and deploy significant capital, and be represented among the market value giants. Over time, however, competition has eroded their advantages, and their Value Ratio has trended towards 1.

However, companies that are now able to secure new sustainable competitive strongholds and hence grow their value over time with a high Value Ratio, can become both value giants and also still be associated with more modest capital employed. Over a period of time, these successful companies will outstrip the growth of companies with a lower Value Ratio. So, any selection of companies on the basis of the size of their market value, like the S&P 500, should increasingly become populated by companies with a high Value Ratio, and hence the average Value Ratio for such a selection should grow over time even though the average for the total market will still be constrained to average around 1 as outlined in section 3.

This has been the case with the S&P 500, which has shown steady growth in the average Value Ratio. This is often shown in inverse, with the excess market valuation over the capital employed referred to as “intangible value”, while the capital employed is referred to as tangible value. As illustrated below, the tangible value has become a small percentage of the total value for market segments increasingly occupying the S&P 500, as would be expected from the previous arguments.

What this indicates is that there are several business areas, like healthcare and information technology, where some companies have been successful in developing new sustainable competitive strongholds that have enabled them to grow large enough to join the S&P 500. This is increasingly difficult in traditional areas like energy and utilities, where historical competitive advantages have already been largely eroded, but some of these high-capital companies are still valuable enough to be included in the S&P 500. Of course, over time, they will probably be displaced from the index as well as faster-growing companies overtake them in value.

In summary, this Newsletter has taken a deeper dive into matters of enterprise value, capital employed, the value ratio and competitive strongholds – considerations for the financial side of making good money. Our next Newsletter will take a closer look at the Value Ratio.

Please note:

The arguments presented in this Newsletter are not providing investment advice or suggesting that you will generally find good investments for your funds wherever you find a high value ratio. Such a high ratio, however, is a signal that a company has been able to generate competitive strongholds of some kind. If you are able to identify the nature of these and subsequently conclude that they are sustainable and expandable, then that may become an indicator of a potentially attractive opportunity.

Question of The Fortnight

Every fortnight, I’ll be asking a thought-provoking question in hopes of sparking interesting and enlightening discussion.

I’d love to hear your response! You can do so by simply responding to this email.

Today’s question is:

Do you find this attention to enterprise value, capital employed, the value ratio and competitive strongholds insightful and potentially helpful in grappling with value generation? Where do you see competitive strongholds being developed?

The Dodo Club Online Course

If you would like to learn more about the kinds of topics covered in these Newsletters, then please consider signing up for the introductory online course.

This covers scenario/systems thinking for grappling with uncertainty, an introduction to energy transitions, and the development of strategic character in leadership.

In the interest of avoiding the fate of that unfortunate bird, the Dodo, this course aims to help us secure our own personal legacies within a changing world and the energy transition - and to leave a healthier planet for future generations.

You can access the course through Udemy using the link below!

A series of follow-up courses that treat the main topics in increasing depth and detail will be provided if there is sufficient interest.